Thanks to research done by Bishop Stone’s great great granddaughter Rosalind Nash Prewett of Dorset, we now can confirm Bishop’s relationships and family tree. This additional information, together with studies done by Robert Hayward, Nan Mead and me since the early 1990s, makes us confident that we now correctly understand Bishop Stone’s ancestry. Please see the archived post on this website dated September 2013 for a statement of the “Bishop Stone Conundrum.” Here are the questions then posed and the answers:

1) Who were John and Mary Stone, the parents of Bishop Stone 1803 and his older brother John 1800 and their two younger siblings Mary and Edmund?

As has long been believed, we can now confirm that Bishop’s father was John Stone 1775, son of John Stone 1739 and Elizabeth Sellick 1750, and a grandson of Thomas Stone 1716 and Betty Perratt 1718. John’s wife Mary was baptized Mary Stone in Brompton Ralph in 1778, a daughter of John Stone 1757 of Lydeard St. Lawrence and Patience Yendell of Raddington. Recent research into Chipstable land records and registers of voters in 1832 and 1846 now confirms that brothers John and Bishop Stone occupied properties that had been in the family of Thomas Stone 1716, then of his son John Stone 1739, and then of his grandson John Stone 1775. These properties include Easter Above Church and Wester Above Church, which were given to John Stone 1739 by his father Thomas and then to John 1775 by his father John 1739.

John Stone 1775 died in 1823 and was buried in Chipstable. The death date of his wife Mary Stone Stone is not certain. Perhaps she died in 1812 when her son Edmund died shortly after birth. Neither John nor Mary Stone were noted as witnesses when their son John married Grace Hancock in 1832 in Morebath, Devon. One would have expected one or both of them to be witnesses had they been alive. Wills are in hand for most of Bishop’s Stone ancestors. For neither John nor Mary has a will been found, suggesting possible unexpected deaths at short notice.

John Stone (1775-1823) had an older brother Thomas (1773-?) and younger brothers William (1779-1804), James (1781-1800), Captain (1784-1821) (my 3X great grandfather), Robert (1786-?), and Joseph (1790-1798)

(2) Who was Robert Stone, the innkeeper at Bampton Inn in Wiveliscombe?

In his 1864 will, Robert Stone the innkeeper provided for his brother John and his nephew Bishop Stone! For some twenty five years, those will provisions quite logically led us to conclude that the innkeeper was Robert Stone 1786 listed above. Robert 1786 indeed was a true uncle of Bishop Stone and brother of John 1775. Thus we determined that he must have been the innkeeper, even though much evidence pointed to Robert the innkeeper having been born in 1790, not in 1786.

While we believed that Robert Stone 1786 was the innkeeper who wrote his will in 1862, the naming of his brother John in the will forced us to question the 1823 burial of John Stone 1775 of Chipstable, even though the burial data appeared to be valid for this John. If John had not died in 1823, however, he would have been 89 years old when Robert’s will was proved in 1864. That age seemed somewhat improbable, but with the additional naming in the will of nephew Bishop, it seemed compelling at the time to conclude that the innkeeper was Robert Stone 1786.

With our recent research in hand, however, it is now certain that the innkeeper was NOT Robert Stone 1786. Indeed, I do not know what became of Robert Stone 1786. His life after being named in his mother’s will in 1804 remains a mystery. The innkeeper whose will is so important to this conundrum was Robert Stone 1790, son of Robert Stone 1744, clothier, and Jane Chorley. Census and tombstone data all confirm that Robert the innkeeper was born about 1790, not 1786. The latest research documents the conclusion that Robert Stone 1790 was the Wiveliscombe innkeeper.

In addition to his proprietorship of the Bampton Inn, Robert the innkeeper was a resident of the Wiveliscombe property called “Weare”, which he had inherited via his father from his grandfather Thomas Stone 1716. The will of Thomas Stone makes this clear. The line of descent to the innkeeper was Thomas Stone 1716\Robert Stone 1744 (clothier)\Robert Stone 1790. It was not Thomas Stone 1716\John Stone 1739\Robert Stone 1786.

Recent research regarding the two Somerset marriages of the innkeeper Robert Stone 1790 confirm the correct ancestry. Both marriages were to widows. Both marriage records state that Robert was the son of Robert 1744, clothier, i.e. not John 1739. According to the parish record in FreeReg, in 1839 Robert was living in Wiveliscombe as a clothier (like his father). He married the widow Maria Timewell in Bishops Hull, Taunton. Her father was Thomas Bowker. In the marriage certificate, Robert’s father was specified to be Robert Stone, clothier.

The widow Maria Timewell was recorded in Wiveliscombe parish records as being Maria Shaddock, the base born daughter of Ann Shaddock. In 1797 Maria married Robert Timewell, and in 1798 they had a son James. In 1861 James was living with his stepfather Robert Stone in Wiveliscombe, stating his age as 63. It appears likely that Thomas Bowker was Maria’s father, as he was named as such in the 1839 marriage record.

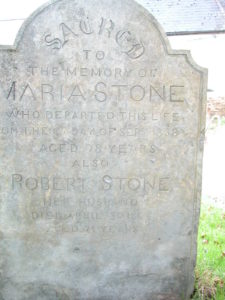

Maria died in 1858 and was buried in the Wiveliscombe churchyard in a site subsequently shared by her husband Robert Stone 1790. In 1861 Robert married another widow, Catherine Gerard, in Weston Super Mare. Catherine was the daughter of Edward Govett Dyer of Milverton. (See FreeReg). Once again, the groom’s father was named as Robert Stone, clothier. It is tempting to speculate that Robert 1790 was visiting John Stone 1789, his first cousin once removed. John was the former Lord of the Manor of Chipstable. After leaving Chipstable, John had become a prominent attorney in Bath and Bristol. He later retired to Weston Super Mare where he died in 1864.

Robert’s second wife, Catherine, died in Wiveliscombe on 10 April, 1865, leaving £1500 to her sister Ann Long in Bristol, described as “her only next of kin.”

So why did Robert the innkeeper name Bishop Stone as his “nephew” in his will, bringing upon us all of this consternation and doubt and requiring many months of additional research?

From the wording of his will, we can accept that Robert did have a brother named John, but as yet we have not yet identified brother John in parish records.

Using current relationship terminology, Bishop Stone was the “grandnephew” of Robert’s father, Robert Stone 1744, the elder clothier. Perhaps Robert 1790 (the younger clothier and then innkeeper) roughly concluded that if Bishop was his father’s grandnephew, he was his nephew. Furthermore, there are those doing genealogical research who counsel us not to take literally the word usage of relationships like “nephew” in documents from the 18th and 19th century. “Jim”, on Somerset Rootsweb, recently advised as follows:

“Relationships in the 19th Century did not have the same meaning as the words we use today. For example son in law was not the husband of one’s daughter but the son of a wife from her previous marriage. Equally, cousin did not necessarily refer to the child of one’s uncle/aunt. Nephew and Niece were sometimes used in reference to one’s God – Children, who may have no blood relationship of any sort. References in wills to “relationships” of modern usage therefore need to be taken with a pinch of salt. “True” blood relationships were usually referred to in the terms son/daughter of my said brother/sister. Anything else needs careful study before drawing conclusions.”

Today we would describe Bishop Stone as the first cousin, one generation younger, of Robert Stone 1790, the innkeeper who wrote the will. Since the true family relationships now are clear and documented, we must accept, as Jim suggested, that the relationship terminology used 150 years ago was not necessarily how we would describe relationships today.

I agree with Jim’s comments regarding “taking with a pinch of salt”. Many of the old Wills I have read refer to “Sisters” who were obviously sister-in-law (married to the blood brother). “Daughters” are daughter-in law, married to the blood related son. My own Gt Gt Grandmother in a census of 1851 is referred by her step father as daughter-in-law after her mother has remarried in Cornwall. So we can clearly see evidence of the practise carried on well into the latter part of 1800’s. Perhaps this usage was more widespread through out England?

My ancestor Mary nee Hunn appears in the family of Abraham Isbel at Tywardreath, Cornwall for both the 1851 and 61 census, as an example of the practise of calling an adopted daughter “daughter-in-law”.